Lack of Regard for Art Education in Schools Google Scholar

Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Chief and Secondary School Educators

ane

Department of Geography, University of Due south Africa, Johannesburg 1709, South Africa

2

GEOMAR, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Ozeanforschung Kiel, 24105 Kiel, Germany

3

Aquatic Systems Inquiry Group, Department of Ecology and Resource Management, Academy of Venda, Thohoyandou 0950, South Africa

4

Centre for Biological Command, Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Makhanda 6140, South Africa

5

Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch Academy, Stellenbosch 7600, S Africa

6

Sustainability Research Unit, Nelson Mandela Academy, George Campus, George 6035, South Africa

7

Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Written report, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa

*

Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: 8 June 2020 / Revised: 13 July 2020 / Accepted: twenty July 2020 / Published: 21 August 2020

Abstract

Plastic pollution is a major global issue and its impacts on ecosystems and socioeconomic sectors lack comprehensive understanding. The integration of plastics problems into the educational system of both primary and secondary schools has oftentimes been overlooked, particularly in Africa, presenting a major claiming to environmental awareness. Owing to the importance of early age awareness, this study aims to investigate whether plastic pollution issues are being integrated into Due south African primary and secondary education schoolhouse curriculums. Using face-to-face interviews with senior educators, we address this research problem by investigating (i) the extent to which teachers comprehend components of plastic pollution, and (ii) educator understandings of plastic pollution within terrestrial and aquatic environments. The results indicate that plastic pollution has been integrated into the school curriculum in applied science, natural science, geography, life scientific discipline, life skills and life orientation subjects. However, there was a lack of integration of direction practices for plastics littering, especially in secondary schools, and agreement of dangers among different habitat types. This highlights the demand for ameliorate educational awareness on the plastic pollution trouble at both chief and secondary school level, with increased environmental programs needed to brainwash schools on management practices and impacts.

1. Introduction

Plastic pollution is a global business organisation that has potentially far-reaching impacts on humans, fauna, soil and ecosystem functioning [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Plastic production has been increasing due to global demands for plastic products in diverse sectors such as domestic, industrial and wellness [7,8]. According to Geyer et al. [9], the durability of plastics makes them an attractive material to use and very resistant to degradation. A recent study estimated global plastic waste production at 6.three billion Mt, with 9% recycled, 12% incinerated (burned) and 79% discarded direct in open dumps and the natural surround [9]. These plastics persist in landfills and the natural environment, which continuously break down into smaller fragments that pose potential risks to humans and fauna [10,11,12]. Further, practices which manage plastics and other waste product by incineration negatively affect air quality and human health, contributing to air pollution and climatic change [thirteen]. Plastics also block drains and littered plastic materials can concord water and create breeding grounds for problematic insect species such as mosquitoes, thus potentially exacerbating the spread of musquito borne diseases [xiv].

Environmental plastic pollution is a challenging restoration and governance issue because it is associated with severe environmental problems, with complex solutions [15]. Furthermore, the costs of waste management activities are a heavy burden for cities and rural localities in developing countries. Several policies, including banning of plastic bags, take been implemented in multiple countries as a strategy for raising awareness and minimizing plastic use, although the effectiveness of these policies is often not visible at a local level [sixteen]. According to African Impact, an organization actively involved in remediating issues of plastic pollution inside the African context, ten rivers in Africa and Asia are the major plastic polluters, which end up in oceans globally (www.africanimpact.com/plastic-ecology-sustainability-programs-africa/). Furthermore, they approximate that 500 aircraft containers of plastic waste are dumped in Africa every calendar month. In South Africa specifically, over ane million tons of plastic waste are thrown away every month. Still, an immeasurable number of towns beyond the continent practise non have an official waste material management system and the few that do generally take poorly managed or broken systems (ibid.). The increment in this environmental trouble also causes educators to perceive effective environmental education equally a stiff response to fight against the environmental crunch [17]. Environmental education provides students with opportunities to connect with circuitous environmental issues, and to develop positive attitudes, noesis, and motivation to take environmental activity [18,nineteen].

With growing environmental problems globally, there has been a concurrent involvement and demand to answer to these bug through encouraging pro-environmental behavior as a pathway aimed towards achieving sustainability goals [20,21,22]. Steg and Vlek [23] highlighted that the quality of the environment is dependent strongly on human beliefs patterns. The norm activation theory conspicuously explains the pro-environmental behavior as being acquired by a chain reaction involving three variables, namely adverse consequence (i.east., awareness of oneself), ascribed responsibility (i.e., sense of responsibleness) and personal norm (i.eastward., moral obligation to do or refrain from a certain behavior), to possible environmental consequences in this instance [24,25]. Thus, pro-environmental behavior for the current report is characterized equally a human beliefs that intentionally seeks to minimize the negative environmental impact of one'due south actions on the natural environment (e.g., plastic reduction, raising awareness and education) [23]. The electric current study aims to examine ecology education behaviors aimed at shaping attitudes, beliefs and values that affect ecology upstanding behaviors through knowledge and skills development, that will enable individuals to participate in supporting an ecologically- and socially-simply club.

Environmental knowledge and attitudes are fundamental elements for irresolute human actions [26]. Efforts have been made to introduce ecology education as a subject, or role of one, in the schoolhouse curriculum across different countries, merely the field of study continuously faces severe limitations and implementation problems [17]. This limitation is mostly due to the lack of applicable and positive ecology attitudes past the schoolhouse educators [17,27]. For effective implementation, educators should exist thoroughly enlightened of ecology pedagogy aspects, as only then tin can they make future generations enlightened of these environmental bug, challenges and their possible solutions [17]. However, it has been noted that in that location is a significant discrepancy between people'due south attitudes and their actual behavior [19,28]. Therefore, information technology has been suggested that educators, being part models, should not only develop a positive attitude but also actually practice ecology protection behavior [19,27]. In turn, this will assistance in developing similar attitudes and actions in following generations.

Plastic pollution awareness should be more effective and efficient, with all stakeholders heavily involved. There is a lack of inquiry regarding strategies and approaches educators are employing to teach environmental pollution, and specially plastic pollution. To address this research trouble, this paper thus aims to investigate whether plastic pollution sensation is being raised in Southward African rural primary and secondary schools. The study specifically aims to (i) appraise whether educators embrace plastic pollution in their school curriculum and find whatever evidence of personal motivation for this on their role to do then; and, (ii) assess the unlike roles played by educators in primary and secondary schools towards plastic pollution education.

2. Methods

two.ane. Research Ethics

Upstanding blessing for this study was granted by the Academy of Venda Research Ethics Committee; number SES/18/ERM/10/1009. All participation in the study was voluntary and the researchers did not in whatsoever way coerce any private into participating. We ensured that informed consent requirements were fulfilled and to help to protect participants' privacy, we applied two common standards: (i) confidentiality and (two) anonymity. In improver, schools where educators had been interviewed were not mentioned by name but were given letters "A" to "D" to ensure confidentiality of information. The data were collected qualitatively using face-to-face interviews, whereby the principal, deputy principal and three senior teachers were interviewed individually.

2.2. Study Expanse

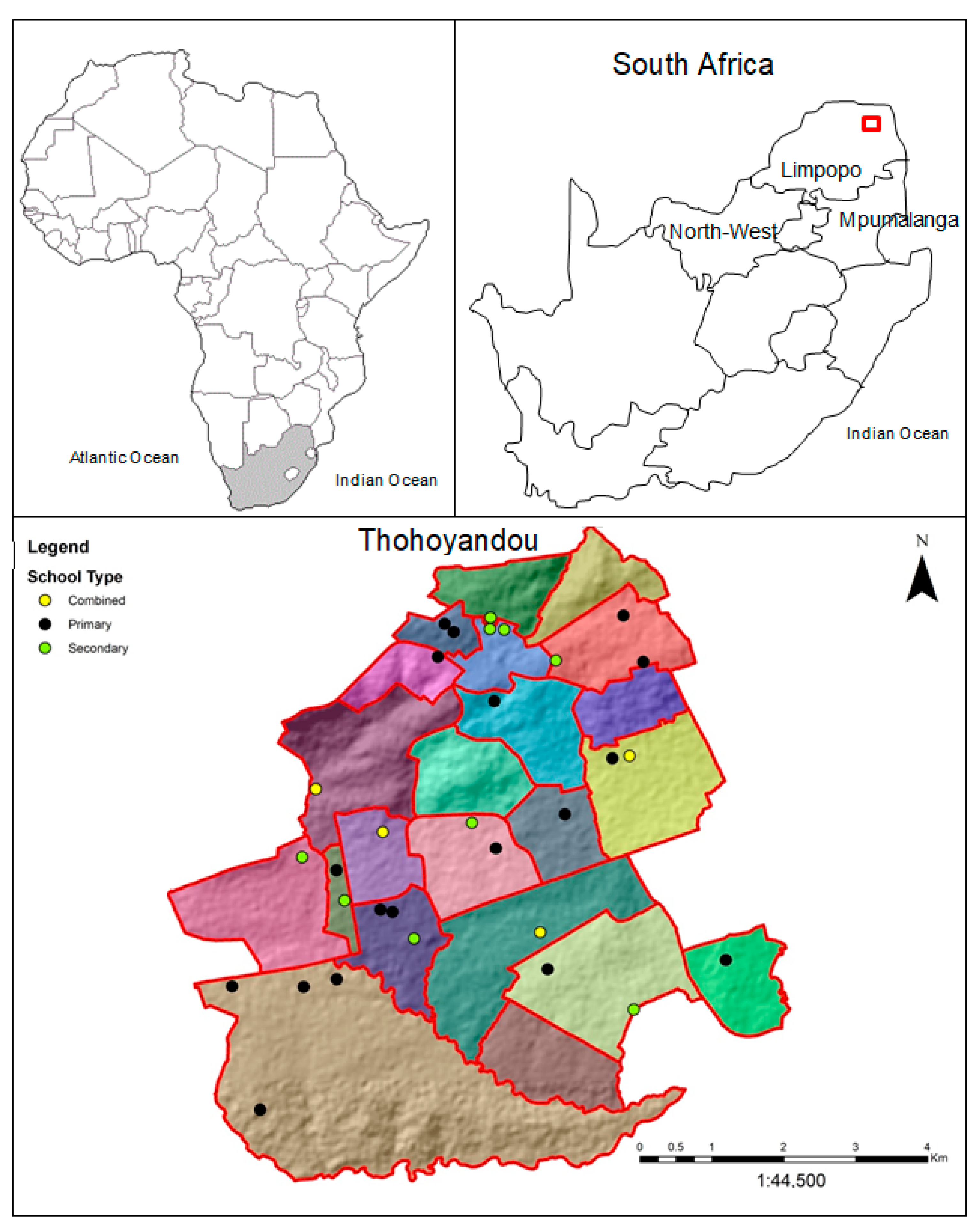

The study was carried out in Thohoyandou, South Africa (Effigy 1). Thohoyandou is located in the Thulamela Municipality, Limpopo Province of Southward Africa, with an estimated household density and population of 17,345 and 89,427, respectively [29]. Information technology is the administrative center of Vhembe District Municipality and Thulamela Local Municipality. The Thohoyandou total expanse coverage is 42.62 km2 and the major economical sectors are commercial and subsistence agronomics. Informal modest trading is one of the most popular concern ventures [29]. The literacy levels are estimated at 76%, with 20% and 4% having secondary and tertiary pedagogy, respectively. 20-seven percent of the population are formally employed with 46% unemployed (Statistics South Africa, 2016). Thohoyandou is considered a "rural town" surrounded by villages, with about 25 master and fourteen secondary schools inside the area. Although the town is considered rural in a South African context, in the wider African context it could be considered modern given the presence of a university, high court and well-developed cardinal concern district. A sample of seven (primary n = 3; secondary n = four) schools was randomly selected throughout Thohoyandou.

2.3. Sampling

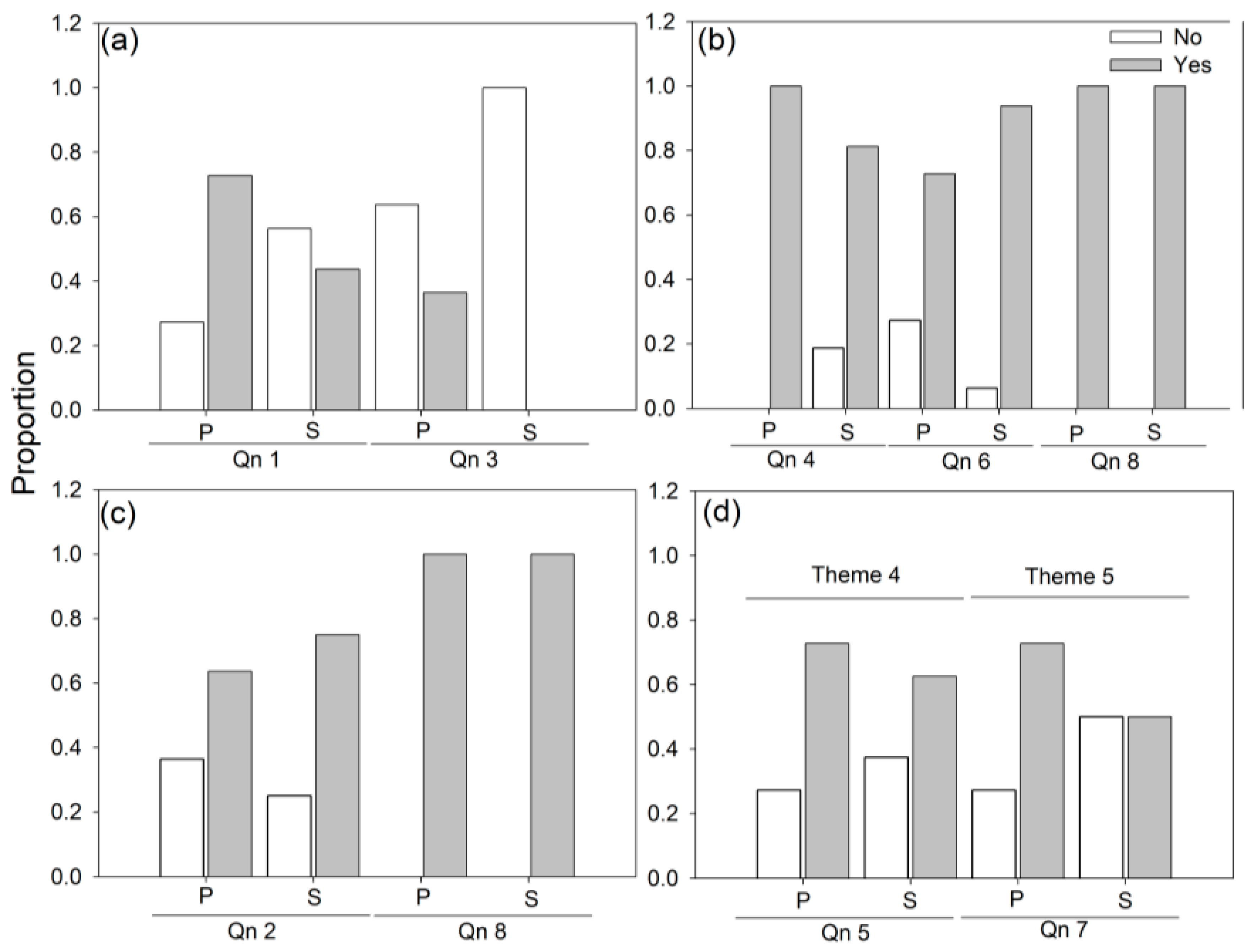

A qualitative arroyo consisting of in-depth, semi-structured interviews (see Table 1) was used to draw and explore interviewees' perceptions to plastic pollution and education, and a full general cess of the educators' general ecology values, knowledge and attitudes, based on the new environmental paradigm approach [30]. Xx-vii (primary due north = eleven; secondary n = 16; Table two) educators were chosen in total, due to their involvement in school decision making processes, overseeing position inside the schools, and/or cardinal roles in developing planning strategies for the school curriculum. That is, educators were selected on the basis of their seniority, with principals or vice-principals included in the majority of schools. After 27 interviews, data saturation was reached to address the specific aims every bit no new or relevant data emerged. Thus, we addressed our findings based on five key research themes that covered a broad array of factors: (i) Schoolhouse environmental policies and codes of conduct (questions 1 and 3), (2) environmental education and awareness (questions 4 and 6), (iii) curriculum development (questions two and 8), (iv) stakeholder partnerships (questions 5), and (five) resource availability (question 7). These themes were selected on the basis of a review of secondary literature to identify major areas across a range of factors.

Face-to-face interviews were administered using the newspaper and pencil instrument method, and too the interviewees were recorded if they approved. In addition, photographs were taken to assess whether awareness on plastic pollution was being raised in schools and if resources were beingness provided towards environmental teaching. The interviews were conducted in either English or TshiVenda with the senior educators for most 30 to 45 min during the 24-hour interval. The raw transcribed data were raised to the unlike thematic levels described higher up using open coding [31] and farther analyzed using the thematic approach described by Braun and Clarke [32] and Clarke and Braun [33].

two.four. Information Analysis

Chi-square analyses were conducted to assess the different levels of perception based on the Likert calibration created for the different interview responses between the principal and secondary school educators within each theme using SPSS version 16 [34]. A two-point Likert scale was used with binary "yep" and "no" responses for each interview question. Split tests were performed for each theme, enabling a comparing of main and secondary schoolhouse environmental education coverages. Nosotros posed the null hypothesis that primary and secondary schoolhouse educator attitudes towards plastics pollution would not differ, with respect to the aforementioned themes.

three. Results and Word

3.1. School Ecology Policies and Code of Conduct

Significant differences (χtwo = xvi.005, p = 0.001) in primary and secondary school educator responses on ecology policy, code of conduct and banned plastics between schools were observed, with secondary schools having the most disagreements on plastic code of conduct and bans, and enforcing fewer policies and bans (Figure 2a and Figure 3a,b). Punishments were imposed on pupils who failed to adhere to the code in but one school. Even though virtually of the educators highlighted that schools had a no littering lawmaking of carry, a visual assessment of the school premises showed that most schools maintained a clean environment (Effigy 3a,b), with the exception of primary schoolhouse B (Figure 3 and Figure 4c).

"Secondary School B, Deputy-primary: Yes, learners are not allowed to throw rubbish everywhere considering nosotros have rubbish bins in front of every class. On Wednesdays, rubbish from the bins must be nerveless. At that place are dire consequences if a learner is establish littering in school grounds."

Schools have introduced plastic bins and instruct learners to employ the bins for litter, thereby reducing the corporeality of plastics and other materials from being dumped into the immediate natural surroundings. However, both chief and secondary school educators highlighted that it was difficult to ban plastics from entering the school bounds equally about of the nutrient items are sold packaged in plastics. Similarly, Adane and Muleta [35] and O'Brien and Thondhlana [nineteen] highlighted widespread use, easy availability, and lack of alternatives every bit key drivers for connected plastic use. Therefore, both studies and the current indicated that there is motivation for promoting pro-environmental beliefs, however the learners' demographic background makes it challenging every bit at that place are few single-use plastic alternatives. Indeed, one primary school teacher highlighted that about learners are from poor backgrounds and mostly utilise plastic containers and bags to shop or carry their stationery, making it difficult to ban non-reusable plastic within the schoolhouse premises. O'Brien and Thondhlana [19] further highlighted that respondents used purchased plastic bags for other purposes similar to the current study. Thus, these learners are in fact promoting the re-apply of plastic bags, but this comes at a cost for the environment as many are not durable, have a loftier turnover and can be easily discarded in the natural environment. Every bit such, the promotion of alternatives for plastic and introducing subsidies could event in low or macerated use of plastic, yet nearly alternatives also come up at a cost for the natural environment [xix,36,37,38,39].

Secondary school B had posters to educate pupils on the need to protect the environment (Figure 3c,d). Hay and Thomas [40] highlighted that posters make sense every bit a means of communicating scientific investigation results quickly and effectively and besides every bit an of import pedagogy and learning aid. Pursitasari et al. [41] observed that students' responses improved when provided with a potent validation through content, presentation, and linguistic communication via books and posters, which also assisted educators in the learning process, and improved students' critical thinking skills on environmental pollutions.

"Secondary, School B, Senior Instructor A: Yes, practise not litter, there are too posters that encourage learners not to throw litter around and trees should be protected as they create a healthy and clean air surroundings."

All secondary school educators highlighted that there were no banned plastic materials within the school premises, whereas 64% of main schoolhouse educators suggested that there were items banned. The observed results might have an impact on the schools and surrounding areas, including the general ecology policy at national and international levels.

"Primary Schoolhouse A, Instructor C: Yes, learners are reminded to pick any plastics and other materials and throw them in the dustbins."

Most of the teachers were not knowledgeable, proactive and enlightened of the dangers of plastic pollution, and were not able to educate learners and take action confronting improper use, purchase and plastic disposal in the natural environment. However, it has been argued that being in positions of authority or existence educated does not promote pro-environmental behavior [42]. Similarly, Kowalski [43] highlighted that some educators were not knowledgeable to plastic pollution prior to training or attention a plastic workshop. In primary school B, there was too a lack of understanding the potential dangers posed by plastics to the environment and also the burning of plastics by the educators.

"Primary School B, Senior Teacher A: Yes, keep the surround prophylactic past non littering in the schoolhouse grounds. For case, burning of plastics and other materials is done after school hours when learners are not present to protect them from inhaling smoke equally information technology will pose a health threat to them."

Integration of plastic pollution issues in the school curriculum could enable teachers to discuss innovative ideas with learners and then that they tin mitigate the problems associated with plastic pollution in the wider environment. Several studies [44,45] are already advocating for greater pedagogy, outreach and awareness within schools equally a mode of protecting the environment and diverse practices may be fostered that lead to unlike perceptions of environmental protection. Thus, the learners would besides exist able to disseminate their knowledge gained with wider communities. Kolwaski [43] highlighted that students and educators more often than not had an improved understanding of plastic-related problems after training, which resulted in changes in behavior and attitudes.

3.2. Education and Awareness

No significant differences (χ2 = x.617, p = 0.059) in main and secondary schoolhouse educators were observed with regard to plastic pollution education and awareness (Figure 2b). Students were encouraged to pick up litter both in master and secondary schools. Thomas [46] noted that behavior change interventions in New Zealand schools resulted in a pregnant reduction in littering rates when used in conjunction with pedagogy, and besides resulted in reduced amounts of plastic being brought into the school premises. In the present study, this was done through four different codes of deport which were routinely identified in principal schools:

"Primary School A, principal…early in the morning time, learners pick up plastics and muddied materials and throw them in the dust bins"

"Chief School C, Instructor A…late comers pick litter in school grounds"

"Principal Schoolhouse A, Teacher C …last yr there was a competition where learners challenged each other on keeping the school free of plastic and papers. In addition, the classes that won were foundation phase classes which start from grade R to grade iii"

- (d)

-

collaboration with solid waste-preneurs;

"Primary Schoolhouse B, Teacher B…there are people who come with bike carts to collect plastic materials and in plow ship them for recycling in commutation for money".

In secondary schools, the above sentiments were too shared by the educators; there were additional programs from outside private and non-governmental organizations which encouraged and instilled a sense of ownership to the environment to learners by teaching them most unlike types of plastics, unlike ways of recycling and the impacts of plastics on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Like to And then and Chow [17], where educators used dissimilar strategies to improve pupils' interest, the involvement of exterior stakeholders tin can significantly improve the students' pro-ecology beliefs. For instance, 1 educator highlighted that:

"Secondary School B, Teacher A…in that location is Limpopo Green Schools for the Earth which is a four-year program whereby learners and communities are role of it. Information technology encourages people to protect water resources as most of the improperly managed plastics cease up in rivers".

With regards to resource available towards environmental education, it was clear that in both primary (73%) and secondary (94%) schools, most educators associated the availability of dustbins (question 6; Figure 4) equally the only form of awareness about proper disposal of plastics. The mode that different schools tackled waste direction could easily be identified by how clean and empty the bins were inside each schoolhouse (meet Figure four) and was a primal forerunner to pro-environmental behavior mental attitude and awareness. In another school, a teacher explained that dustbins are labelled in a mode that depicts which type of waste is to be disposed in them.

"Primary Schoolhouse A, Instructor A…dustbins are provided in the school yard so that plastics don't end up in the basis."

"Secondary School, Teacher C…in that location are plenty dustbins around the schoolhouse and are classified on what waste is tending."

Encouraging waste recycling in schools past educators has been found to generally improve students' attitudes and behavior towards general waste and the natural surround [22]. All the same, concerns have been raised that, despite the availability of rubbish bins, some students still do not throw waste matter in designated bins as they associate picking upwardly waste with being the cleaners', janitors' and/or intendance takers' chore. Similarly, Kanene [47] and And so and Chow [17] highlighted that environmental education has failed to transform students' attitudes towards responsible and action-oriented ecology stewardship.

"Secondary School A, d/principal … the school has bought bins but learners lack interest on the outcome of throwing litter in the bins. The reason behind is that they await cleaners to option upwardly the litter as information technology is part of their jobs."

All educators in both schoolhouse types were very much aware of the impacts of plastic pollution in the environment, and aware of the plethora of challenges that emanate from the use of plastics. Teachers gave examples which showed that plastic pollution impacts the society at different scales. In master schools, concerns about the probability of children suffocating as a result of improper disposal of plastics were raised.

"Chief School C, d/principal…considering we are living in a dingy environs, and then we should alert learners on the dangers of plastics every bit information technology may impairment them in one way or the other. For instance, children might encompass their faces with plastic and stop up suffocating thus dying."

Whilst the dangers of plastics on different land uses were raised:

"Primary School C, Instructor A…considering plastics have been a global problem which results in expiry of birds, fish and livestock".

For instance, one respondent mentioned that stray dogs and browsing goats that enter the school premises accept suffocated later ingestion of plastics (" Secondary School A, principal…because plastics may suffocate animals, for case lingering goats and dogs that enter the schoolhouse premises might consume them and end upwardly suffocating"). Whilst, other respondents cited that plastics are non-biodegradable and that burning of plastics results in toxic gases being released into the air, contributing to the greenhouse event.

"Secondary School B, Teacher C…information technology is important because locally people burn plastics and other waste which releases dangerous gases that harm human health. Inhalation of gases released contributes to diseases such as asthma and lung diseases. In add-on, burning of waste also adds the amount of heat in the surround which results in global warming."

It is also interesting to note that in the secondary schools, burning of plastics was considered a way of disposing of plastic waste.

"Secondary Schoolhouse C, Teacher A…there are dustbins and a site where plastics and other waste are burnt."

This is despite several studies [48,49] highlighting that plastic waste incineration was a major source of air pollution, and ~12% of plastics burnt released toxic pollutants which impact the climate, and threaten plant, animal and human wellness.

3.3. Curriculum Development

Responses from principal and secondary schools to theme three differed significantly for both question 2 and question eight (χii = 10.058, p = 0.018) (Tabular array 1, Figure 2c). Overall, responses in both primary and secondary schools suggested that pollution as a general concept was accommodated inside the existing curriculums, and educators had the opportunity to teach on the subject matter. Withal, it seems that the event of plastic pollution is rarely taught and therefore, educators should be encouraged to train students to think about the environs in the context of the man body and health [l]. Several studies [51,52,53,54,55] have shown that students do not have sufficient cognition to contribute to the development of ecology awareness habitats/attitudes. However, the latest changes in school policy and curricula confirm that the relevance of environmental education has been recognized around the world [54,55,56], merely changes in school practise are lacking. Out of a total 27 responses in the present study, nine reported that no attribute of plastic pollution specifically is taught within the curriculum. This was mostly observed in the responses given past main schoolhouse teachers. Only the class 7 teachers indicated that in that location was specific curricula content covering plastics:

"Primary schoolhouse A, Teacher C: Yep, in grade 7 in that location is a topic of matter and materials whereby learners are taught almost the manufacturing of plastics and the environmental impacts they accept on the environment."

Curriculum content for secondary schools covered aspects of pollution, and mostly water pollution rather than plastic pollution. Pollution was generally covered in the applied science subjects, with life orientation besides having components of pollution. Not all students study engineering in secondary school, however, and this potentially limits the awareness on plastic pollution to all students and teachers. For instance, in European countries, Stokes et al. [57] and Stanišić and Maksić [54] pointed out environmental education is taught as a standalone subject or embedded within other subjects. Linguistic communication teachers, for example, pointed out that they practice not take any content on pollution in their subject area. It is of import to notation that other areas such as Hong Kong allow educators to design their own school-based curriculum, where they are incorporating plastic pollution in all subjects given its importance as an everyday effect [17,53]. The people of Hong Kong waste product millions of plastic bags and this waste material causes an enormous pollution problem, and thus, plastic bag pollution was chosen equally a lesson topic equally it is a familiar issue with school students [17,53].

All secondary and master school teachers felt it was important for them to teach nearly plastic pollution, however the reasons for this varied. Although there was variation in the motivation for education plastic pollution, all teachers displayed noesis on the general problems of plastic pollution, which include the difficulty of plastic disposal due to the not-biodegradable nature, the dangers to aquatic and terrestrial animate being, negative effects on aesthetics and their release of toxic gases if wrongly tending of by burning. A senior fellow member of staff did, however, point out that although educators responded in the affirmative to the importance of teaching on problems of plastic pollution, their own behavior seemed to contradict their beliefs:

"Secondary school C, deputy principal: Aye, it is vital to ensure a green footprint, however, teachers practice address the dangers of pollution, yet they (the teachers) litter daily…"

This observed beliefs by the deputy primary highlights the challenges in trying to implement the pro-environmental behavior within schools when the educators have a negative attitude towards pollution i.east., littering.

3.4. Stakeholder Partnerships

Our results showed no significant differences (χ2 = iii.307; p = 0.579) between master and secondary schools in terms of the existence of stakeholder partnerships or networks that promote environmental awareness (Figure 2nd). The Un Sustainable Development Goal number 17 recognizes the importance of partnerships and collaborative governance in solving escalating ecological problems, pregnant that collective chapters and knowledge roles are disquisitional in finding key solutions [58,59]. Thus, organizations in the civil society, individual and public sectors are experiencing force per unit area to address complex environmental challenges through collaborative activity via multi-stakeholder partnerships. Mannathoko [60] observed that school-stakeholder partnerships provide an effective approach in curriculum evolution and implementation, and further promote students' academic success and effective schooling in Botswana. The study further revealed benefits of schoolhouse-stakeholder partnerships due to educators' express skills in the thing. In chief schools, the majority of the respondents agreed that there were networks within the area that played an important function in promoting environmental sensation. Indeed, private companies and volunteers within the community were institute to exist frequent networks mentioned in past primary school educators. In secondary schools, reference was made to the diverse programs that already existed in the customs. For case, in response to the being of networks that promotes awareness, i respondent said:

"Secondary School C, Deputy Principal: Yes, there is Thohoyandou Victim Empowerment Programme (TVEP) that raises awareness on social problems and are addressing environmental bug. For example, improper disposal of disposable nappies has impact on the environmental and human well-being equally it ends up on roads and nearby rivers."

3.v. Resource Availability

Our results showed no significance differences (χ2 = i.395; p = 0.238) between primary and secondary schools in resources availability that promotes environmental sensation (Figure second). Liefländer and Bogner [61] observed that organization noesis may also influence utilization, i.e., students who desisted from (ab)using nature also seem to put more effort into improving their ecology knowledge, and/or students who engage in learning about the environment will become less exploitative towards the surroundings. Thus, it should be noted that the environmental knowledge promotion is often viewed equally a fundamental ecology education component and an essential prerequisite to ecological behavior; however, it has little outcome on actual private behavior [62]. Resource allocated towards environmental education in the sampled schools include textbooks, dustbins and posters. Environmental protection pedagogy textbooks and posters take been highlighted to play a significant office in students' pro-environmental beliefs [41]. Dustbins are the virtually utilized resource allocated in every sampled school as they brainwash learners regarding where to throw litter, thus making the firsthand environment look tidy. However, learners and educators often ignore throwing litter in the bins provided and litter the school ground instead. Such individualistic behaviors take been attributed to most environmental problems [63] and demand to change in order to movement towards more environmentally responsible schools and sustainable societies [64]. Otto and Pensini [62] farther observed that increased nature-based environmental teaching participation was related to greater ecological behavior, mediated by increases in environmental knowledge and connexion to nature which was defective from the educators.

Every bit such, issues related to resources availability cannot be neglected. Our results also show that on one hand, students are educated in the context of pro-environmental behavior (for example, how to separate reduce, recycle and reuse), whilst on the other hand, the schools exercise not make it feasible to practice this behavior past non providing the necessary resources. Although bins were commonly mentioned to exist bachelor, most schools did non accept clearly labelled bins for separating waste product (for instance, plastic, newspaper, organic waste product). These structural changes are needed in both primary and secondary schools, which concurs with Kullmuss and Agyeman FF [65].

four. Conclusions

The results bespeak that plastic pollution has been integrated into the school curriculum in technology, natural science, geography, life science, life skills and life orientation subjects. However, there was a lack of integration of management practices for plastics littering, especially in secondary schools, and understanding of dangers amongst dissimilar habitat types. The present written report thematically identifies key areas relating to plastics pollution awareness and management which are defective in principal and secondary schools. Therefore, environmental programs that include emerging pollutants such equally plastic among private, non-governmental organizations and government should exist adult to assistance students to better understand the interactions between human activities and the natural environment, likewise as the ecology problems they confront locally and globally. Hereafter enquiry should additionally: (i) examine the perspectives of learners also equally educators when examining the efficacy of environmental education programs; (ii) aggrandize inquiry into many schools across dissimilar countries/regions to gain a better understanding of plastic pollution additions to the schoolhouse curriculum, and; (iii) further assess the relationship betwixt environmental teaching and educators' ecology perception in regards to learners' beliefs. It is also important to note the side by side generation cannot contribute sufficiently to alleviating these problems in their daily lives and will demand the input of all stakeholders in the private and public sectors. Thus, the teaching of all other stakeholders in the round economy (i.eastward., consumers, designers and manufacturers) on the whole process surrounding pollution is additionally important. Nevertheless, at that place are several challenges and opportunities that exist within ecology education with regards to plastics in schools, as indicated in the present study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, 1000.T.B.D. and T.D.; methodology, M.T.B.D., T.D., R.N.C, L.D.C.; software, M.T.B.D. and T.D.; validation, M.T.B.D., R.N.C., H.M., 50.D.C., C.M., A.One thousand. and T.D.; formal assay, M.T.B.D., R.N.C., C.M., A.M. and T.D.; investigation, Thousand.T.B.D., H.M., and T.D.; resources, K.T.B.D. and T.D.; data curation, M.T.B.D., H.M. and T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.B.D., R.North.C., H.M., C.Grand., A.M. and T.D.; writing—review and editing, M.T.B.D., R.N.C., H.G., L.D.C., C.Yard., A.Grand. and T.D.; visualization, Chiliad.T.B.D., R.Due north.C., L.D.C. and T.D.; supervision, M.T.B.D. and T.D.; project administration, Thou.T.B.D. and T.D.; funding acquisition, T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Academy of Venda Niche Grant (SES/18/ERM/x) and N.R.F. Thuthuka Grant (117700) and the APC was funded by University of Venda.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and National Research Foundation of South Africa, respectively. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no disharmonize of interest.

References

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, Chiliad.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from country into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of droppings on marine life. Mar. Pollut. Balderdash. 2015, 92, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettipas, Southward.; Bernier, 1000.; Walker, T.R. A Canadian policy framework to mitigate plastic marine pollution. Mar. Policy 2016, 68, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, J.; Bail, A.L.; Avery-Gomm, South.; Borrelle, South.B.; Bravo Rebolledo, E.50.; Lavers, J.L.; Mallory, M.L.; Trevail, A.; Van Franeker, J.A. Quantifying ingested debris in marine megafauna: A review and recommendations for standardization. Anal. Methods 2017, nine, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.; An, Y.J. Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, T.; Malesa, B.; Cuthbert, R.N. Assessing factors driving the distribution and characteristics of shoreline macroplastics in a subtropical reservoir. Sci. Full Environ. 2019, 696, 133992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amélineau, F.; Bonnet, D.; Heitz, O.; Mortreux, V.; Harding, A.M.; Karnovsky, North.; Walkusz, W.; Fort, J.; Gremillet, D. Microplastic pollution in the Greenland Sea: Background levels and selective contamination of planktivorous diving seabirds. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, R. Prospect of recycling of plastic product to minimize environmental pollution. Encycl. Renew. Sustain. Mater. 2018, i, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics always made. Sci. Adv. 2017, iii, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.M.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, R.N.; Al-Jaibachi, R.; Dalu, T.; Dick, J.T.; Callaghan, A. The influence of microplastics on trophic interaction strengths and oviposition preferences of dipterans. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2420–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbedzi, R.; Dalu, T.; Wasserman, R.J.; Murungweni, F.; Cuthbert, R.Northward. Functional response quantifies microplastic uptake by a widespread African fish species. Sci. Full Environ. 2020, 700, 134522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavropoulos, A.; Newman, D. Wasted Health: The Tragic Example of Dumpsites; Report Prepared as a Part of International Solid Waste product Association's Scientific and Technical Commission Work-Plan 2014–2015; International Solid Waste Clan: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, North.; Kumar, A.; Majgi, S.M.; Kumar, G.S.; Prahalad, R.B.Y. Usage of plastic numberless and health hazards: A study to assess awareness level and perception nigh legislation amongst a pocket-size population of Mangalore city. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, x, LM01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvergne, P. Why is the global governance of plastic failing the oceans? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 51, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-utilise plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.W.Chiliad.; Grub, S.C.F. Environmental education in master schools: A example study with plastic resources and recycling. Education 3-13 2019, 47, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizmony-Levy, O. Bridging the global and local in agreement curricula scripts: The case of environmental education. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2011, 55, 600–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.; Thondhlana, Thou. Plastic bag use in Southward Africa: Perceptions, practices and potential intervention strategies. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.; Keizer, M.; Steg, L.; Maricchiolo, F.; Carrus, Chiliad.; Dumitru, A.; Mira, R.Thou.; Stancu, A.; Moza, D. Ecology considerations in the organizational context: A pathway to pro-ecology behaviour at work. Free energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Yeung, K.50.; Carrico, A.R.; Gillis, A.J.; Raimi, Chiliad.T. From plastic bottle recycling to policy support: An experimental test of pro-environmental spillover. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, C.C.; Cheung, T.Y.; Then, W.W.Grand.; Cheng, I.N.Y.; Fok, L.; Yeung, C.H.; Chow, C.F. Enhancing pupils' pro-environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours toward plastic recycling: A quasi-experimental study in primary schools. In Environmental Sustainability and Pedagogy for Waste Management; So, Westward., Chow, C., Lee, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-ecology behaviour: An integrative review and inquiry calendar. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of sensation, responsibleness, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyamin, A.; Djuwita, R.; Ashar, A.A. Norm activation theory in the plastic age: Explaining children'due south pro-environmental behaviour. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 74, 08008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.E.; Rickson, R.East. Environmental knowledge and attitudes. J. Environ. Educ. 1976, eight, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molstad, East.P.; Heyer, G.P.; Martin, K.; Sardi, P. Reducing single-use plastic in a thai school community: A sociocultural investigation in Bangkok, Thailand. Available online: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/206 (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Van Rensburg, M.L.; South'phumelele, L.Northward.; Dube, T. The 'plastic waste product era'; social perceptions towards unmarried-use plastic consumption and impacts on the marine environs in Durban, South Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 114, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Southward Africa (Stats SA). Census 2016: Achieving a Meliorate Life for All: Progress Between Census' 2007and Census 2016 (No. 3); Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.Eastward.; Van Liere, Thou.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological epitome: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Problems 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczyk, G.; De Matteo, D.; Festinger, D. Essentials of Enquiry Pattern and Methodology; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. two. Enquiry Designs; Cooper, H., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, The states, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In Encyclopaedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Enquiry; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Kingdom of the netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Release 16.0.0 for Windows. Polar Engineering and Consulting; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, United states, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adane, Fifty.; Muleta, D. Survey on the usage of plastic bags, their disposal and agin impacts on environment: A case study in Jimma Metropolis, Southwestern Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2011, iii, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chanthawong, A.; Dhakal, Due south.; Kuwornu, J.K.; Farooq, M.K. Impact of subsidy and taxation related to biofuels policies on the economy of Thailand: A dynamic CGE modelling approach. Waste material Biomass Valor. 2018, xi, 909–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, C.; Feng, L. Environmental governance strategies in a two-echelon supply chain with taxation and subsidy interactions. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 290, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.Due north.; Royals, A.W.; Jameel, H.; Venditti, R.A.; Pal, L. Evaluation of paper straws versus plastic straws: Development of a methodology for testing and understanding challenges for newspaper straws. BioResources 2019, 14, 8345–8363. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, A.; Simpson, A.; Neeman, T.; Dickson, K. Plastic bag bans: Lessons from the Australian Capital Territory. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, I.; Thomas, S.M. Making sense with posters in biology didactics. J. Biol. Educ. 1999, 33, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursitasari, I.D.; Suhardi, Due east.; Fitriana, I. Development of context-based education volume on environmental pollution materials to improve critical thinking skills. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Man Res. 2019, 253, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, K.P.; Chan, H.W. Ecology business concern has a weaker association with pro-environmental behaviour in some societies than others: A cross-cultural psychology perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M. Mitigating Microplastics: Development and Evaluation of a Middle School Curriculum. Main's Thesis, Oregon Land University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T.R.; Pettipas, Southward.; Bernier, M.; Xanthos, D.; Day, A. Canada's Dirty Dozen: A Canadian policy framework to mitigate plastic pollution. Zone Fall Declension. Zone Can. Assoc. Newsl. 2016, 9–12. Available online: https://www.researchgate.cyberspace/profile/Tony_Walker/publication/311732880_Canada\T1\textquoterights_Dirty_Dozen_A_Canadian_policy_framework_to_mitigate_plastic_marine_pollution/links/5858032608aeabd9a589e1b5/Canadas-Dirty-Dozen-A-Canadian-policy-framework-to-mitigateplastic-marine-pollution.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Karpudewan, M.; Roth, Westward.Thousand. Changes in primary students' informal reasoning during an environment-related curriculum on socio-scientific issues. Inter. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2018, 16, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.M. Environmental Engagement through Behaviour Change Interventions: A Case Study of Litter Reduction in New Zealand Schools. Principal'south Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanene, K.M. The affect of environmental education on the environmental perceptions/attitudes of students in selected secondary schools of Republic of botswana. Eur. J. Altern. Educ. Stud. 2016, 1, 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.; Vinoda, K.S.; Papireddy, G.; Gowda, A.N.South. Toxic pollutants from plastic waste matter—A review. Proc. Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essienubong, I.A.; Okechukwu, E.P.; Ejuvwedia, S.Thou.; Essienubong, I.A.; Okechukwu, Due east.P.; Ejuvwedia, S.G. Furnishings of waste dumpsites on geotechnical properties of the underlying soils in moisture season. Environ. Eng. Res. 2018, 24, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, H.M. Medical school curricula should highlight ecology health. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.B. Evaluating Environmental Educational activity in Schools. A Practical Guide for Teachers; Environmental Education Series 12; Environmental Education Section, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gayford, C. Environmental education in schools: An culling framework. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 1996, 1, 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, A.N.H. Plastic bags and environmental pollution. Art Educ. 2010, 63, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanišić, J.; Maksić, S. Environmental didactics in Serbian primary schools: Challenges and changes in curriculum, pedagogy, and instructor training. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.; El Batri, B.; Zaki, M.; Nafidi, Y. Ecology education in Moroccan primary schools: Promotion of representations, cognition, and ecology activities. Elem. Educ. Online 2019, 19, 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello, P.; Fernandes, R.C. Bibliographic review of articles on pedagogical practice of ecology education in schools. Terrae Didat. 2019, 14, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, E.; Border, A.; West, A. Environmental Instruction in the Educational Systems of the Eu: Synthesis Report. Available online: http://www.medies.net/_uploaded_files/ee_in_eu.pdf (accessed on vi May 2020).

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, Fifty.; Roseland, M.; Seitanidi, Thou.M. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG# 17) as a means of achieving sustainable communities and cities (SDG# 11). In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Enquiry; Filho, Westward.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kandziora, J.H.; Van Toulon, N.; Sobral, P.; Taylor, H.50.; Ribbink, A.J.; Jambeck, J.R.; Werner, S. The important role of marine debris networks to prevent and reduce sea plastic pollution. Mar. Pollut. Balderdash. 2019, 141, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannathoko, M.C. School-stakeholder-partnership enhancement strategies in the implementation of arts in Botswana basic education. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2019, xv, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.Ten. Educational touch on on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, Due south.; Pensini, P. Nature-based ecology education of children: Ecology noesis and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.C.; Waliczek, T.Thousand.; Zajicek, J.Grand. The relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental mental attitude of high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 30, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Collaboration as a Pathway for sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 16, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure ane. Location of the different principal and secondary schools institute inside Thohoyandou town, Limpopo Province of South Africa. The unlike colored areas stand for the various residential areas/suburbs.

Figure 1. Location of the different primary and secondary schools found within Thohoyandou boondocks, Limpopo Province of South Africa. The different colored areas represent the diverse residential areas/suburbs.

Figure 2. Ii-signal Likert scale (yes/no) responses, expressed as proportions, gathered from the 27 senior staff educators from principal (P) and secondary (S) schools interviewed for the five themes: (a) theme ane: environmental policy, (b) theme two: education and sensation, (c) theme 3: curriculum development, and (d) themes 4: stakeholder partnerships and v: resource availability. For question (Qn), come across Table one.

Figure ii. Two-point Likert scale (yes/no) responses, expressed every bit proportions, gathered from the 27 senior staff educators from primary (P) and secondary (S) schools interviewed for the five themes: (a) theme 1: environmental policy, (b) theme 2: pedagogy and awareness, (c) theme 3: curriculum development, and (d) themes 4: stakeholder partnerships and v: resource availability. For question (Qn), see Table 1.

Figure iii. Methods initiated at selected schools to heighten sensation among students inside school premises: (a) Do not litter sign (primary school C), (b) school code of conduct sign with environs-related points 3 and 14 (primary school C), (c) educating students on environment (secondary school A), and (d) an environmental awareness chart in one of the class rooms (secondary schoolhouse A).

Figure 3. Methods initiated at selected schools to heighten awareness among students within schoolhouse premises: (a) Exercise not litter sign (primary school C), (b) schoolhouse code of behave sign with environment-related points 3 and fourteen (main school C), (c) educating students on environment (secondary schoolhouse A), and (d) an environmental sensation chart in one of the class rooms (secondary school A).

Figure 4. Maintained and empty bins in (a) main school C and (b) secondary schoolhouse B, full and un-maintained bins (c) and (d) in master schoolhouse B in the Thohoyandou area, South Africa.

Figure 4. Maintained and empty bins in (a) main school C and (b) secondary school B, full and united nations-maintained bins (c) and (d) in master school B in the Thohoyandou surface area, South Africa.

Table ane. The study interview questions administered to chief and secondary educators.

Table i. The study interview questions administered to primary and secondary educators.

| Number | Question | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| one | Are There Whatsoever Environmental Policies in the School that Y'all are Aware of? | one |

| 2 | Within the curriculum is at that place whatever content that allows you to teach about pollution and specifically plastic pollution? | three |

| 3 | Are there any banned plastics in the school? | one |

| 4 | Are in that location whatever extra curricula activities or programs that increment environmental awareness such equally picking upward litter around the school of recycling? | 2 |

| 5 | Does the school have any networks with NGO's that promote environmental awareness? | 4 |

| six | Are there any resources (i.e., environmental sensation posters, flyers) allocated towards environmental education? | 2 |

| 7 | Exercise teachers consciously cull to utilize non plastics materials when they are teaching? | 5 |

| eight | Do teachers experience information technology is important to teach about pollution and the specific dangers to the environment? | iii |

Table ii. Twenty-seven different senior staff members interviewed during the study from 3 primary and 4 secondary government schools from Thohoyandou, Limpopo Province, Southward Africa.

Tabular array ii. Twenty-7 unlike senior staff members interviewed during the study from iii primary and iv secondary regime schools from Thohoyandou, Limpopo Province, S Africa.

| Primary | Deputy Principal | Senior Teacher | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||

| Primary | |||||

| A | x | ten | x | x | 10 |

| B | ten | x | |||

| C | x | x | x | x | |

| Secondary | |||||

| A | x | 10 | x | x | x |

| B | 10 | ten | x | ten | |

| C | ten | x | ten | x | x |

| D | ten | x | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open admission commodity distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/17/6775/htm

Post a Comment for "Lack of Regard for Art Education in Schools Google Scholar"